Homelessness Investments Outcomes; Public Comment Meeting re: SR 99 Tolls; Books for Teachers

Homelessness Investments Outcomes

A couple weeks ago, I promised an update on how funds invested by the Human Services Department were spent on in homelessness in 2017 and what were the outcomes.

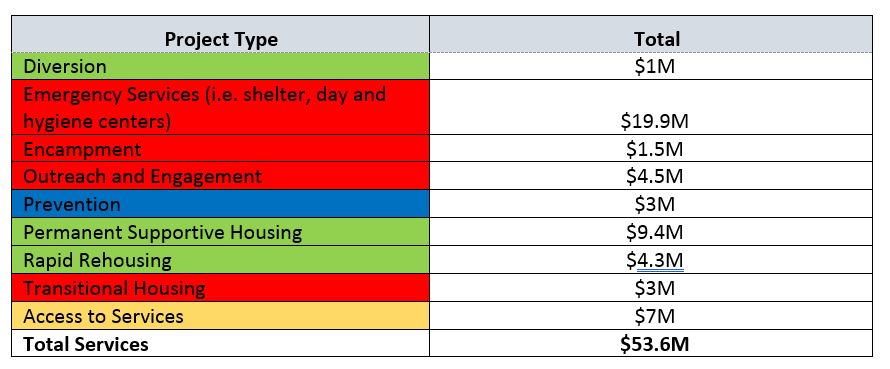

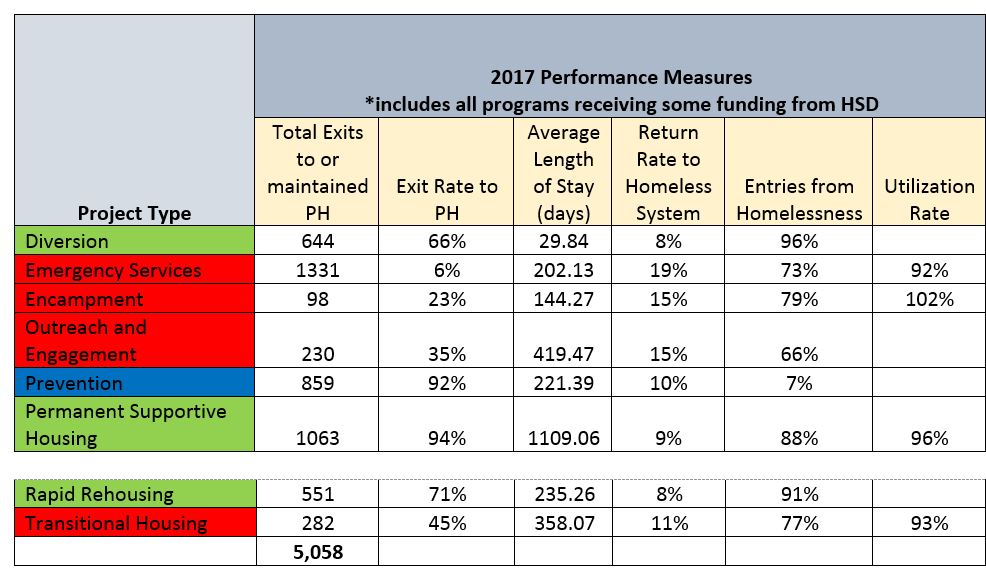

In 2017, HSD invested $54 million in prevention, emergency and housing services for people experiencing homelessness. CBO identifies $61M in total spending for homelessness, and this includes items such as Domestic Violence and Sexual assault services and Healthcare for the Homeless through King County. These city-supported projects helped 5,058 people in the homeless services system to either move to permanent housing or maintain their permanent housing. This is a 30% improvement over 2016 outcomes and with increased investments in housing, prevention and enhanced emergency services in 2018, HSD expects that the city’s funded programs will have an improved rate of success in 2018.

For 2017, the results for the performance measures are as follows:

It’s important to note here that though HSD predicts continued improvement, the King County audit cautions that hope without significant investments in permanent housing is unsupported:

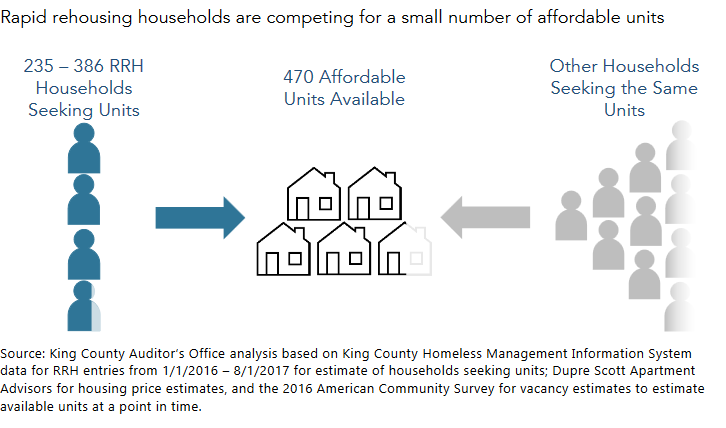

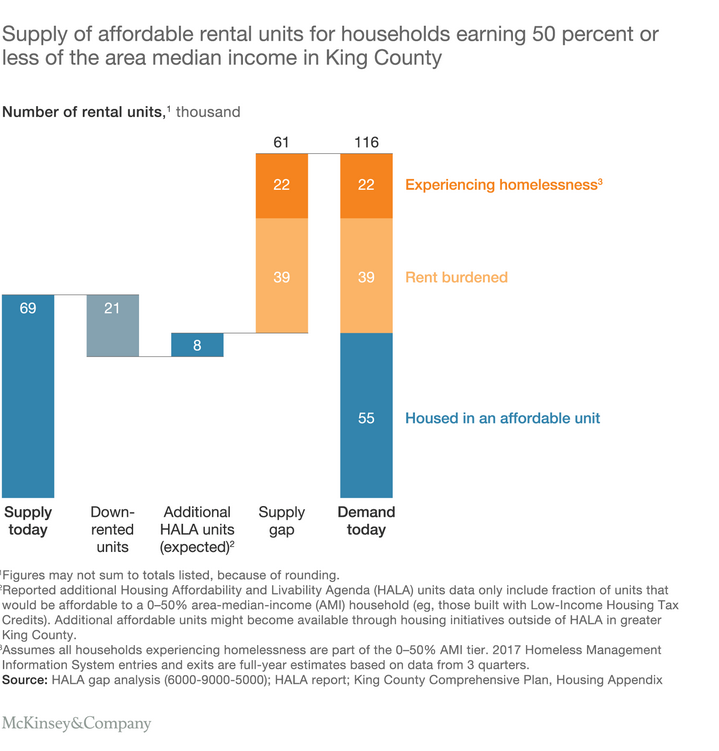

“Local funders have increased investments in rapid rehousing (RRH), but past performance, market challenges, and limited information raise concerns about its potential limitations. RRH performance in King County has consistently fallen below national benchmarks and local standards, and fewer than half of enrollees got housing through a RRH program between January 1, 2015 and August 1, 2017.Those who do not get housing are less likely to exit to permanent housing and more likely to return to homelessness. Competition for limited affordable housing makes it difficult to move rapid rehousing clients into units. In King County, there are on average 470 one-bedroom units and studios affordable to households making less than 30 percent of area median income at a time. Since 2016, RRH providers have sougth these types of units for an average of between 235 and 386 households at a time (see Exhibit I). This means that providers would need to be able to place clients in half to over three quarters of these available units, with constrained conditions for larger households as well. Given that other households compete for these same market units, finding units that RRH enrollees can occupy is a challenge.”

I get a lot of questions from constituents about homelessness. Here are some of my responses to the kinds of questions that I frequently get.

- Why isn’t homelessness being solved on the regional level?

- How long should it take to move a homeless person into a shelter?

- Isn’t addiction the real reason for homelessness?

- Can’t we solve homelessness through zoning changes?

- Why can’t we do what other successful cities have done to combat homelessness?

- Why can’t we draw on more non-profits, churches, synagogues and mosques to offer temporary housing?

- We need to have homeless people do their share. There must be some reciprocity – if we help them, then they need to (clean up garbage, agree to drug treatment etc.)?

- Why are we allocating more resources to the homeless and ignoring law-abiding citizens? RVs can park any time anywhere, but we get parking tickets.

- We spend more per capita on the homeless than most other cities to no effect.

- Camping on the street is still more affordable than the units being planned. The City doesn’t stop people from doing this so what motivation would they have to change?

- There isn’t enough funding put into mental health services or drug addiction – these issues impact homelessness too.

- It’s the City’s policies that have created the homeless problem. The City attracts the homeless because of our lax policies.

- Two years ago, a study was undertaken to develop a plan to deal with the homeless and evaluate the financial needs of doing so. The conclusion was that the city had enough money to handle the issue but were not allocating it appropriately.

- Why isn’t homelessness being solved on the regional level?

Homelessness is a regional problem and one that extends beyond our City limits. As our partners in combating a crisis, we look forward to the regional One Table’s recommendations and fully expect the County and others to engage in addressing this massively increasing, too. It must be a regional effort if we are to be successful.

The city needs to keep maximizing the leveraging of additional new resources that is be forthcoming from the State, as well as the County, to increase the number of housing units serving homeless persons. Here are some new regional resources that we expect to help Seattle in 2018:

- $40 million in 2018 from the State for behavioral health, including crisis intervention, opioid treatment and overdose prevention, and detox facilities.

- $5.7 million in 2018 from King County for the expansion of emergency shelter and safe alternatives for people living outdoors in two locations in Seattle.

- How long should it take to move a homeless person into a shelter?

It depends on the type of intervention, but according to City performance metrics the maximum amount of time that it should take to move someone out of a sanctioned encampment is 90 days. A recent audit conducted by King County showed that the average time a prioritized household waits between assessment and housing referral was twice as long as the federal standard. The study said that the primary reason for this was that “Long waits are due in large part to a shortage of homeless housing. Given the current homeless housing stock and vacancy rate, even if no one else joined the community queue, it would take more than seven years for everyone to secure housing. In the entire county, only about 1,120 homeless housing units become vacant each year. Meanwhile, by the end of September 2017, there were 8,299 homeless individuals and households awaiting housing referral.”

It is important to note that this study only measured how the system fell short for prioritized populations according to a vulnerability assessment. There are many people who are not prioritized that may never get on a list for permanent housing.

- Isn’t addiction the real reason for homelessness?

Addition can be one factor in homelessness, but not the only one. Significant increases in rent make it more difficult for low-income people to find housing. 25 years ago, Seattle was well-known as a center of heroin addiction, but there were significantly fewer homeless people, as rent was inexpensive.

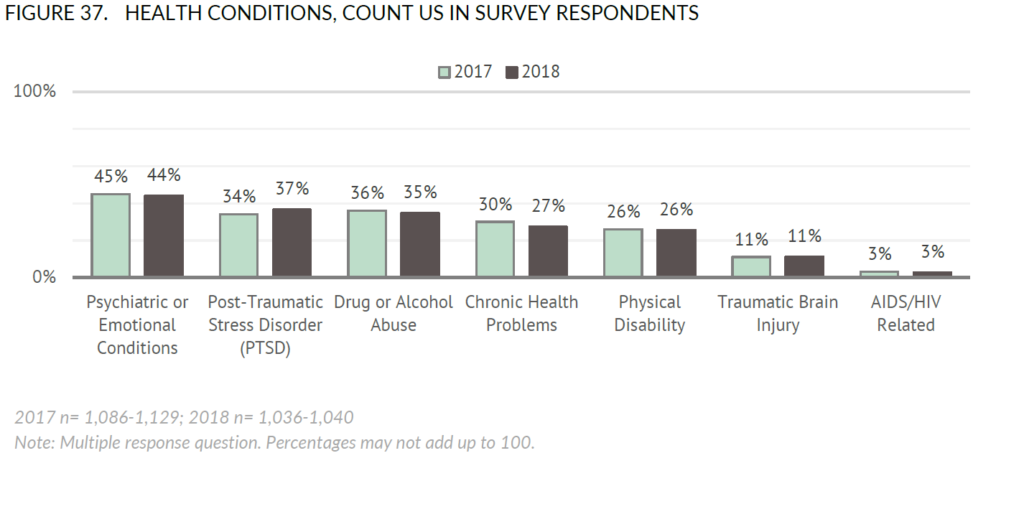

Half of Count Us In survey respondents “reported at least one disabling condition, and among those individuals 33% reported living with two or more disabling conditions. Behavioral health conditions were the most frequently reported disabling conditions among Count Us In survey respondents, with 44% experiencing psychiatric or emotional conditions, 37% living with post-traumatic stress disorder, and 35% reporting drug or alcohol abuse.”

- Can’t we solve homelessness through zoning changes?

The City Council is considering the Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) proposal, to increase allowing building in exchange for more affordable housing. It takes time to build, however, so this, or other zoning changes, won’t provide a short-term solution. MHA will only contribute about 6,000 units of affordable housing over the next 10 years, far less that the recent McKinsey Report identifies as the housing gap: “Even assuming, somewhat unrealistically, that all new affordable housing currently planned by the city of Seattle was made available without delay, we estimate there would be a supply gap of 60,000 homes.”

- Why can’t we do what other successful cities have done to combat homelessness?

Often when people ask why Seattle can’t mirror programs that have been successful in other cities, they are referring to programs such as Utah’s Housing First Model. The Housing First approach was actually designed in Seattle, specifically the Downtown Emergency Service Center (DESC) with its project 1811 Eastlake. Housing First is already a cornerstone of the King County All Home Plan, and the 10-year plan before that. DESC’s 1811 Eastlake saved taxpayers more than $4 million dollars in the first year of operation. But that was just the first recognized Housing First project in Seattle, since then, the jurisdictions and funders planning to end homelessness in King County (including – among others – Bellevue, Renton, Redmond, Shoreline)– as a matter of policy – actually prioritize funding for projects that also use the Housing First model.

To end homelessness in Washington State using the Housing First model, we need a massive investment in Housing First. The recent the McKinsey/Seattle Chamber of Commerce report demonstrates that despite the Chamber’s claims that we only needed to spend our money more efficiently, that in order to make a meaningful impact on the crisis, the region would need to increase regional annual spending by approximately $164 to $215 million annually, and spend 85% of that on building housing. It’s not that we need to follow the example of states like Utah, rather we must have the political will to fund more of what we know works because of our own experience.

- Why can’t we draw on more non-profits, churches, synagogues and mosques to offer temporary housing?

About 11 religious facilities throughout the City offer shelter to approximately 350 people each night. There is interest to try to expand the number of non-profits and religious organizations offering temporary housing. I, too, welcome more participation. The Progressive Revenue Task Force recommendations agree we should encourage more, here is what they said:

Many faith communities throughout Seattle devote significant labor, space, money, and other resources to help their homeless neighbors and to address the homelessness crisis. The City should recognize and leverage these contributions, and in general be more deliberate in its relationships with faith communities. The City could provide small grants to assist their work and/or establish ways of better communicating and coordinating with faith communities that are doing this work.

- We need to have homeless people do their share. There must be some reciprocity – if we help them, then they need to (clean up garbage, agree to drug treatment etc.)?

The 2016 Comprehensive Homeless Needs Assessment done by Applied Survey Research interviewed 1,050 unsheltered individuals in November 2016. They surveyed people living on the streets, in encampments, and in public shelters to further understand their situations and needs, and to better inform the City’s responses with its partners. 41% of survey respondents experiencing homelessness reported they were employed.

There are also several Seattle-based organizations that work to provide the homeless with employment opportunities including:

- The Seattle Conservation Corps, a program that’s been providing employment for people experiencing homelessness since 1986, for more than 30 years. Watch for the folks with the orange vests picking up garbage around the courthouse.

- Metropolitan Improvement District program, for concierge services (including street cleaning). These are the folks you’ll see downtown wearing yellow jackets. It is also partially supported with City of Seattle funding. Here is a good article.

- The Millionaire’s Club jobs program for homeless folks in Seattle with a little different focus.

- YouthCare, which has 4 different homeless youth employment programs:

- Why are we allotting more resources to the homeless and ignoring law-abiding citizens? RVs can park any time anywhere, but we get parking tickets.

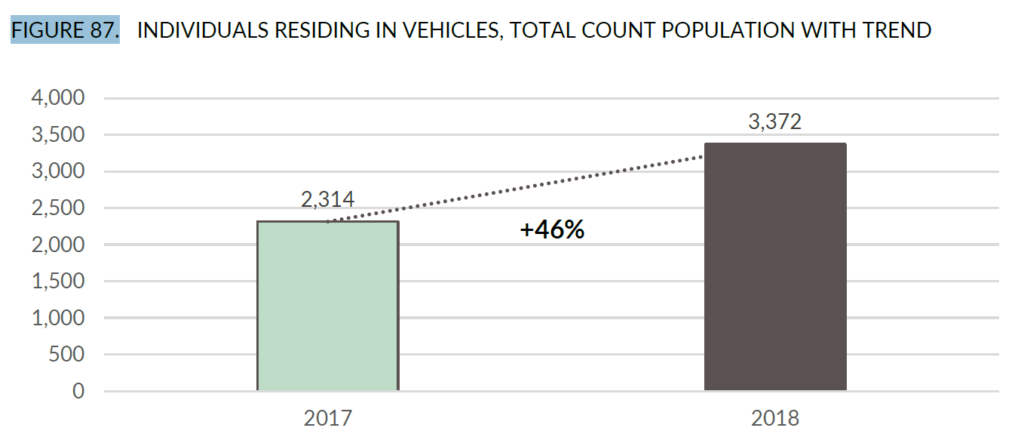

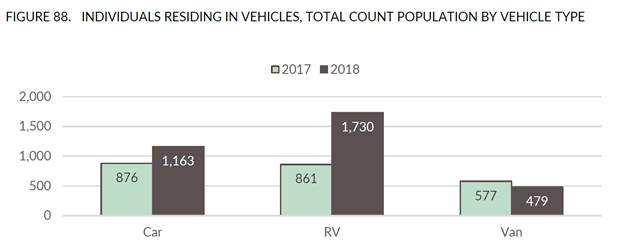

The 2018 King County Count Us In Report found that an estimated 3,372 individuals living in vehicles. These individuals comprised 28% of the total count population and 53% of the unsheltered population.

Since RVs often violate parking laws, the Police Department is the lead agency for dealing with RVs. A recent lawsuit is requiring law enforcement all over Washington State and California too, to reconsider how they enforce laws against parking in an area for more than 72 hours when it is apparent that the vehicle is someone’s home. Nevertheless, in addition to addressing one-off situations, the Police Department and SPU are leading an interdepartmental team to clean up 4-6 problem RV sites each month.

There are three ways to file a complaint regarding trash, needles, unsanctioned encampments, safety or RV/Car campers violating the 72-hour parking law:

- online: Service Request Form

- mobile: Find It, Fix It mobile app

- phone: 206-684-2489 (CITY)

- We spend more per capita on the homeless than most other cities to no effect.

I have found an unsupported quote from an individual running for public office about per capita spending on homelessness in King County. I have found no studies to support the claim that Seattle’s spending on homelessness ($86/per capita) exceeds other large, high cost cities.

For instance, New York City, where there is a right to shelter, roughly $530,000 per day, or $364 million a year, is spent on hotel rooms for the homeless. NYC’s annual funding is $2.3 billion (about $315/per capita) for their shelter programs, their hygiene programs, or the homelessness prevention or diversion program. Another example is Los Angeles, which spends $440 million a year to address homelessness (about $110/per capita), and San Francisco that spends $279 million a year on homelessness (about 323/per capita).

- Camping on the street is still more affordable than the units being planned. The City doesn’t stop people from doing this so what motivation would they have to change?

The city works to connect homeless people who are living unsheltered with resources that provide temporary or permanent housing. Part of this effort includes the creation of the Navigation Team who monitors and provides outreach services in unsanctioned encampments. The team conducts daily outreach to unsanctioned encampments throughout the city and determines which encampments should be scheduled for removal. The team also offers a variety of services in unsanctioned encampments including referrals to safe living alternatives, referrals to medical or service providers, help obtaining identification or benefits, accessing employment support, connections to legal resources, offering mental health support, safe storage and delivery of personal belongings, and even participation in a trash pick-up program to reduce the public health threats.

The City removes between 3-6 encampments each week. More than 70 encampments removed since January of this year alone. There are, at any given time more than 400 complaints about unique encampment locations at any given time. The City has a process for:

- Prioritizing encampments for removal.

- Providing notice when an encampment is scheduled for cleanup.

- Offering outreach and alternative shelter options.

- Cleaning up an encampment site.

- Collecting, cataloguing and storing personal belongings and how individuals can recover their property.

- Immediately removing obstructions and immediate hazards.

- Identifying and specifying emphasis areas that will be subject to daily inspection and immediate removal of any encampment-related materials.

- There wasn’t enough funding put into mental health services or drug addiction – these issues impact homelessness too.

The Navigation Team does provide mental health support to the homeless community when it conducts outreach, but Washington State and King County are ultimately responsible and have the authority for providing mental health and drug treatment services.

- It’s the City’s policies that have created the homeless problem. The City attracts the homeless because of our lax policies.

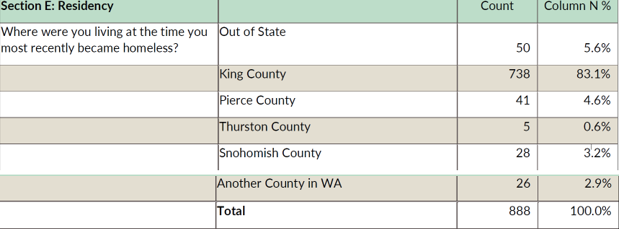

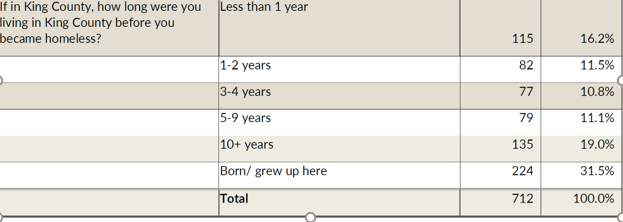

I don’t agree that Seattle’s homeless policies are attracting people to come and live on our streets homeless, without electricity or running water, no place to secure ones’ belongings, or wash, go to the bathroom, and dispose of their garbage all the while being vulnerable to crime. The vast majority of people, 83.1%, who are homeless in King County had King County as their last address when housed, and of those people 31% were born/grew up in King County.

- Two years ago, a study was undertaken to develop a plan to deal with the homeless and evaluate the financial needs of doing so. The conclusion was that the city had enough money to handle the issue but were not allocating it appropriately.

Two years ago Barb Poppe, an homelessness consultant, wrote a report on Seattle’s homelessness crisis, which became the basis for the set of recommendations known as Pathways Home. Poppe 2016 study, in which she stated that no additional funds should be needed, relied on data from 2014. In 2017, Poppe admitted that the homeless population in Seattle had grown since 2014 and additional resources might be needed, and Seattle was mostly allocating its money in a way that aligned with her previous recommendations.

Washington State Transportation Commission Public Comment Meeting June 5 re: SR 99 Tolls

When the state legislature voted in 2009 to have WSDOT replace the Alaskan Way Viaduct with a tunnel along the Downtown Seattle waterfront, it required $400 million of the $2.4 billion in state funding to come from tolls. In 2012 the legislature reduced this to $200 million. The legislature also required funding to operate and maintain the tunnel to come from tolls, an additional $170 million.

On May 22nd, the Washington State Transportation Commission (WSTC), which under state law sets toll rates for state highways, released three options. All three options include tolls that vary by the time of day, from $1 on weekends and overnight, to $2.25 during evening rush hour.

The WSTC will be holding public comment meetings in early June. The West Seattle meeting will be on Tuesday, June 5th at High Point Community Center (6920 34th Avenue SW). An open house is planned from 5:30-6:30, with public input from 6:30 to 8 p.m. More information is available here, including about meetings Downtown on May 4th and in Phinney Ridge on May 6th.

Comments can also be e-mailed to transc@wstc.wa.gov, by phone at 360-705-7070, or by postal mail to Washington State Transportation Commission, PO Box 47308, Olympia, WA 98504.

Details about the toll rates for each of the options, by time of day, are on the WSTC’s SR 99 tolling fact sheet; additional background is available at their SR 99 Tunnel Toll Rate Setting webpage.

The WSTC applied the following objectives in determining the options, as required by a state law that was passed by the state legislature in 2012:

- Minimize diversion, particularly during initial years of tolling as downtown Seattle construction limits capacity of alternate routes;

- Support facility performance and the customer experience;

- Provide sustainable toll rates that meet all legally required financial obligation

The WSTC will gather public comment through early July, and is scheduled to advance an option for final public review at their July 17/18 meeting in Olympia. They plan to take final action to adopt toll rates during the fall of 2018.

WSDOT uses tolls for other major projects, including the SR 520 bridge, which has tolls that vary between $1.25 and $4.30 by time of day; the Tacoma Narrows Bridge has a toll of $5; tolls on I-405 vary by time of day, between 75 cents and $10, based on real time traffic conditions.

The tunnel could open as soon as this fall; at first, there will be no charge. The state hasn’t decided yet how soon tolls will begin.

Once Alaskan Way is rebuilt after the removal of the Alaskan Way Viaduct, a new exit just before the tunnel entrance will lead to Alaskan Way.

Below is brief background on the tunnel project and the state legislature’s requirement for tolling; earlier tolling studies were completed in 2010 and 2014, as noted below.

PROJECT HISTORY

In 2001, after the Nisqually earthquake, WSDOT began an evaluation of multiple options to replace the Alaskan Way Viaduct, including 76 initial conceptual alternatives, and detailed analysis of five alternatives in 2004.

In 2009 the state legislature approved a funding plan for a tunnel to replace the Alaskan Way Viaduct. The legislation found that the Alaskan Way Viaduct “is susceptible to damage, closure, or catastrophic failure from earthquakes and tsunamis” and that replacement was “a matter of urgency for the safety of Washington’s traveling public and the needs of the transportation system in central Puget Sound.”

The funding plan included $400 million from tolls (later reduced to $200 million), and required WSDOT to do a tolling study, including an examination of potential diversion of traffic onto city streets.

The tolling report required by the legislature was completed in 2010. It concluded that peak period tolls could range from $2.75 to $5 in 2015 dollars.

In 2011 the City Council created a “Alaskan Way Viaduct and Seawall Replacement Program Advisory Committee on Tolling & Traffic Management” to advise the City and State. They examined seven options in their 2014 report, and found that a rate lower than the 2010 report would be sufficient.

Subsequently WSDOT’s Toll Division began an investment-grade traffic and revenue study, which is needed to issue the bonds that tolls will finance. Subsequently, the WSTC released options on May 22nd.

Previous WSDOT environmental documents and reports for the Alaskan Way Viaduct and Seawall Replacement Project from 2004 to 2015 can be found here.

Are you a teacher at a Title 1 school? Do you know one? Friends of the Seattle Public Library, thanks to funding from the Renee B. Fisher Foundation, is able to grant teachers at Title 1 Seattle Public Schools up to 100 free books from the Friends of the Seattle Public Library’s stock of used children’s books.

Any teacher at a Title 1 school within the Seattle Public School system can apply for the program, and access is first come first serve. There are two events a year for teachers to come and select their free books. The next event is on Saturday, June 30.

All teachers at Seattle Title 1 Public Schools are invited to apply, just send an email to booksforteachers@friendsofspl.org and say you’re interested in participating in the Books for Teachers program. Include your full name, the name of your school, and the grade level(s) you teach. For those that are not accommodated with 2018 grant funds, you will be put on a priority list to be invited in 2019.

Posted: June 1st, 2018 under Councilmember Herbold, Education, Homelessness, Human Services, Libraries, Parks and Recreation, Public Health, Seattle Public Utliities, Transportation

Tags: free books, homelessness, housing services, parking, prevention, RV, teacher, Title 1 school, tolling, transportation, tunnel project, WSTC